Doreen Ríos (1/2): Technical, Tactical, and Technological Disobediences—«Understanding that other nature of the technical object, that ‘second life’ of the object.»

Cover: Portrait of Doreen Ríos / Photo: Courtesy of the curator.

Interview: Nicolás Kisic Aguirre / Editing: Yeudiel Infante & Nicolás Kisic Aguirre

In May 2024, we connected via Zoom to talk: Doreen Rios from San Diego, where she is pursuing her PhD in art history, and me from Seattle, where I was pursuing mine at DXARTS. I prepared myself by reading Doreen’s texts, such as Unpacking Mexican Media Art1 and her essay on Dataspace, which were in direct dialogue with the questions that guide Disobedient Robots.

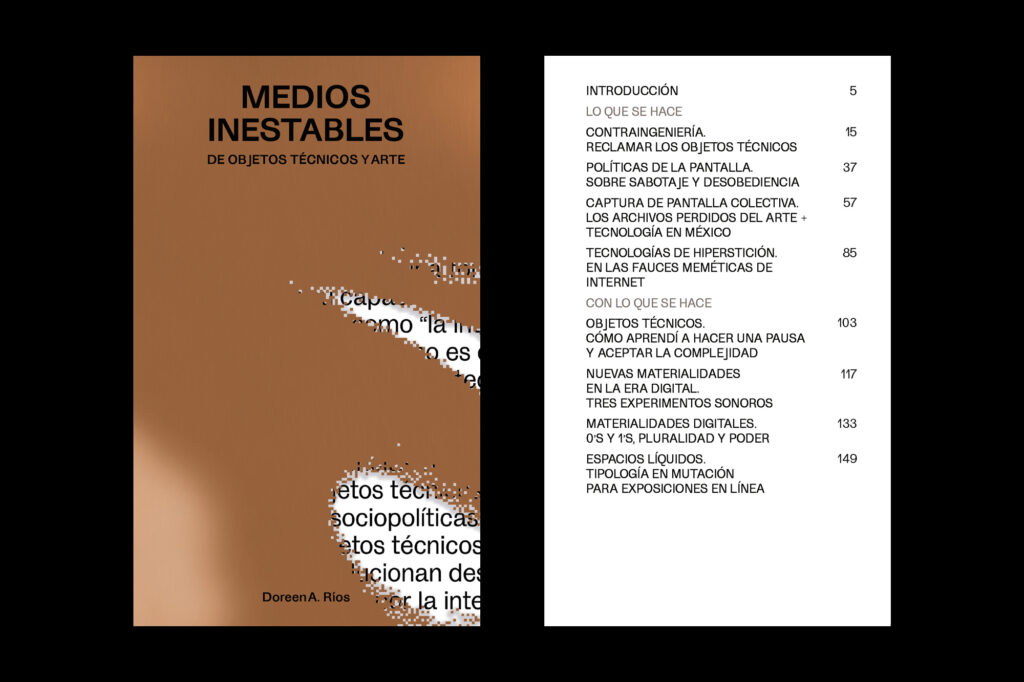

Today, more than a year later, the publication of this interview coincides with the appearance of the book Medios Inestables. De objetos técnicos y arte (A Coruña: Bartlebooth, 2025), in which many of the ideas in this interview are developed at greater length.

In this first part, our conversation quickly circled around technological disobedience, collective imaginaries, and the ways in which technical objects acquire new lives in Latin American contexts. From there, a space opened up to think about how these practices, tactics, and acts of reappropriation also reconfigure the way we understand robotics from an artistic perspective.

Nicolás Kisic Aguirre: Doreen, thank you very much for this time to connect. Beyond questions and answers, I would like to be in dialogue with you about issues based on some texts you have shared with me, such as the one on Unpacking Mexican Media Art, which I found very interesting, with many points in common. Or the one you wrote about Dataspace, the exhibition that took place both in Mexico and in Madrid. Honestly, I am fascinated by and deeply inspired by what you have written. You have researched “technological disobedience,” particularly in the Mexican context. On my end, the project I am developing is titled Disobedient Robots. Obviously, [Disobedient Robots] is closely connected to all of these references, since in many countries across Latin America we have gone through similar contexts of crisis, both economic and political, and in many cases this ends up shaping the spectrum of technological and vernacular possibilities.

From your point of view, from your curatorial background and knowledge of the art and technology spectrum, both Mexican and Latin American, what do you understand when you read or hear the phrase “disobedient robots”?

Doreen Ríos: “Disobedient Robots” makes me think of the production of objects that solve very concrete tasks, but that do not necessarily follow the predesign of their parts. Of course, I am simplifying quite a bit what “technological disobedience” is: an exercise in reappropriation, reuse, and reinvention of existing technologies. If we take this very specifically into the realm of robotics, I would understand it, to begin with, as reappropriated, reinvented, or reused objects that do not directly respond to their predetermined forms or objectives. And that is what seems truly central to me when thinking about technological disobediences in a broader sense. It is a negation or a resistance, but above all, an expansion of the possibilities of the technical object.

When I think about robots, I think of everything from a blender to that image of humanoids with metallic parts so prevalent in science fiction and popular culture. But of course, there are also all these other little robots that surround us. Blenders, the coffee maker, the refrigerator… And all the points in between expand the idea of what “disobedient robots” could be.

I think it emerges from the question: what else can it be? [This object] already is, already works, already solves a task, but what else can it be? That same object, in alliance with, in expansion with, or decontextualized for something else. I think a lot, for example, about the whole culture of short tutorials. Hacks.

NKA: Short Instagram tutorials, five-minute hacks, right?

DR: Even less! I think of this video that went very viral, of a man combing his daughter’s hair and using a vacuum cleaner to pick up her ponytail. I think that maybe now we see these things through that kind of content, or we notice them in everyday life through those short-form pieces, mainly on platforms where this kind of content is produced en masse and replicated ad infinitum. All of those hacks or novel, different, or atypical ways of using the “robots” that surround us in daily life, when I see them, they make me laugh a lot, because I think, maybe we had never given them a name from Latin America, but this is absolutely and completely natural, right? In your text

NKA: The TV set, the fan, everything…

DR: Maybe it is not about giving it a new function, but about expanding its function. My dad is not necessarily looking for a kind of disobedience that negates the object’s use, but he is definitely expanding how it can be used in other ways. That is what I imagine when I think about “disobedient robots.” Those expansions, reappropriations, and modifications aimed at asking what else this object can do, or what else it can be.

NKA: Interesting! The other day I was talking with Leo Núñez, an Argentine artist. He works extensively with robotics; he was here visiting Seattle and we had a very good conversation. He spoke to me about the collective imaginary. He said that we all share a collective imaginary of what a robot is, one that is somewhat defined by science fiction, by Hollywood, and so on. He does an exercise [in workshops for children] in which he asks them to close their eyes and imagine a robot. They begin to imagine something very similar to what you were describing a moment ago: the classic science fiction robot, with a certain kind of voice, made of tin, humanoid in appearance, but never quite human.

In contrast, I find it interesting how you are now talking about social media platforms, where perhaps a different collective imaginary is beginning to take shape. The dominant discourse may start to be punctured by the possibility of producing one’s own imaginaries at home, and by the idea that, suddenly, a robot could also be everything else. I think it is important to be able to construct or reconstruct that collective imaginary from “the South”, rather than so easily jumping onto the bandwagon of the robotic imaginary that came from science fiction and that is, in fact, relatively recent.

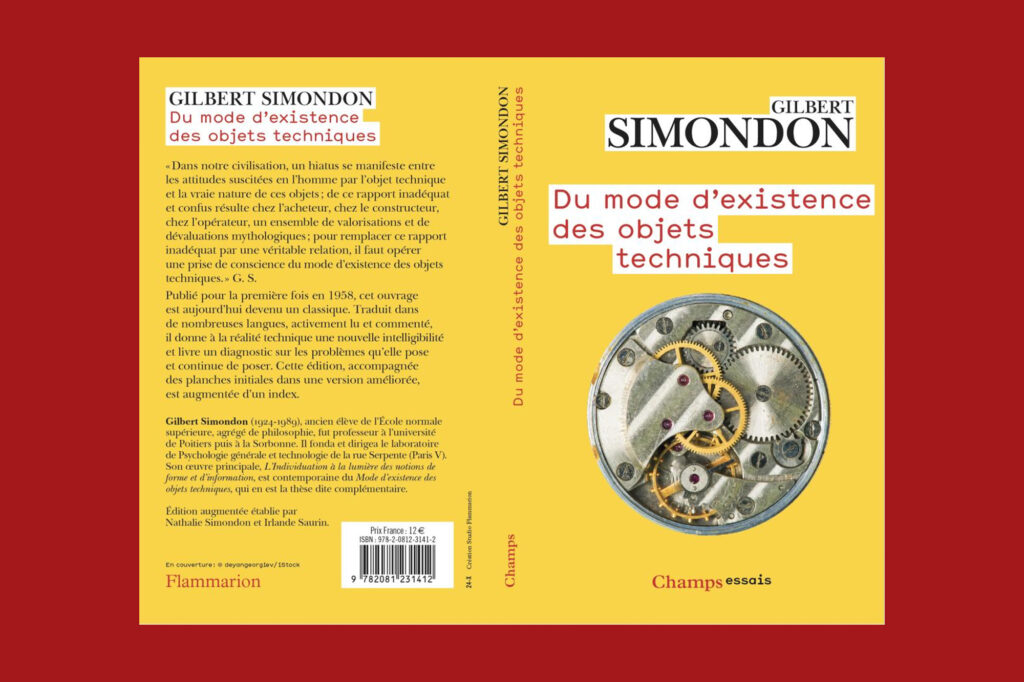

You write in your text3 about Simondon and about the definition of the “technical object” that inspired and struck you, and about how that definition of the “technical object” perhaps entails the non-definition of technical objects themselves, that is, that they are in constant evolution. Through their use and their relationship with people and cultural contexts, technical objects take on new meanings, moving from being “pre-individuals” to “individuals.” But the process never stops; it does not come to an end. I find this fascinating, and I think it could be key to creating other collective imaginaries. That is, not having a single function or a clear definition of what objects are or what they are for, but rather engaging with all of their possibilities [indefinitely].

I think the West has a strong tendency to package, close off, divide, and deliver things already finished [objects], right? And one, passively, says, “okay, fine, let’s consume.” [When] in reality, we always have the possibility of redefining them.

DR: Yes, that seems central to me. How can we imagine a methodology that analyzes not only practices of technological disobedience, but also any creative practice that incorporates the use of different technical objects in its execution, production, or presentation, or all of them? I think that one of the major challenges in understanding what is happening there, even in philosophical terms, is precisely the challenge of multiplicity.

I find Simondon’s notion of the technical object very useful, particularly his proposal to divide it into two parts: the abstract technical object and the concrete technical object, and how, in their final conjunction, the process of individuation of the technical object can be articulated. It is not one or the other separately; it is both. At the moment when they come together, this third thing occurs: the process of individuation. I feel that, in many cases, the way technical objects are read, regardless of context, is almost exclusively from the abstract domain: what they were designed for, with what intentions, their final uses, what problem they are meant to solve, right? That is, everything that is predesigned and prepackaged in the objects per se. But if we never make that transition from the desire or idea of the technical object in its abstract form to its concrete form, where it begins to acquire a series of meanings very different from those originally embedded in its production, design, or conceptual framing, then we truly cannot arrive at a way of approaching the totality of the technical object’s process of individuation.

To me, especially in the arts, there is a rather detached approach when it comes to trying to understand that other nature of the technical object, that “second life” of the object. Because the technical object in its concrete form, even when it is used in the way it was intended to be used, that is, when a person goes and buys a blender and actually uses it to blend their food, even in that case there are many elements within its concrete form that begin to enter into dialogue with, or come into tension with, the original abstract forms that were projected onto the object per se. But when, in addition to that, the object, in its concrete form, is not used for what it was prepackaged for, predesigned for, and so on, something much more complex emerges, something that becomes difficult to analyze when we have not even stopped to really think about how these two elements converge [the abstract and the concrete].

[There can be a great deal of complexity] even when these objects are used in the way they were intended or designed to be used. I am thinking especially about very complex technical objects, about which Simondon obviously does not write, because they did not exist at the time he was developing his ideas. These are technical objects that, drawing in part from Lev Manovich4, I refer to as meta-tools. The computer, the tablet, the smartphone. That is, when the technical object, at the abstract level, no longer has a single function, but multiple functions as an organic part of its design. The computer, for example, which perhaps this meta-tool, at its beginnings, was something like…

NKA: …Initially it was like a converted typewriter?

DR: It was originally a message decryption machine, right? In a way, an algorithm-decryption machine. Later, it becomes an archive machine, containing a series of elements that anyone can go to and retrieve or access, or a machine for calculation. So what happens when this machine turns into a meta-machine, one that is not only the place where you work, but also where you learn, where you deploy your affects toward other people, where you entertain yourself, and where you shop? All of that is already pre-designed into the machine. That is, we are not even talking yet about anything that disobeys those multiple functions. I think that when we try to extrapolate this to the field I currently research, which is art history, we run into an enormous problem at the very level of how we understand the object itself, because we had never previously encountered that kind of multiplicity, one that is constantly expanding, constantly flexible, and constantly changing.

In fact, I would even go so far as to say that, from the very first digital technical objects—which, by the way they are created, already allow for this multiplicity of actions—it becomes impossible to generate an ontology of the object per se, because we are always speaking in epistemological terms. It is a bit the same problem Barthes has with photography. That is, Barthes struggles again and again with the question: what is the ontology of photography?5 Not the photographic act… not the result of the photographic act. What is photography? He never really resolves it. And I think that, despite the fact that photography is still a technical object with a specific function—the production of images—it is already a complex proposition, but it is *one* single function. Now, when you make that exact same reading of a technical object such as a computer, where it can be whatever you want, right—where it encompasses all functions—well, if Barthes, working with photography, never managed to arrive at a determination of its ontology, then there is no way we are going to get to the bottom of the ontology of the digital technical object, because it is no longer even part of its original design.

It’s a very complex and very in-depth conversation, but, to simplify, what I think we need to start doing is recognizing which abstract and concrete elements are involved in the tools being used, in this case, for artistic production. This can be understood as a kind of acknowledgment of what we are actually doing. On the one hand, for example, we might say: “we’re working with a computer,” fine. Who made the computer? What year is it from? Where was it manufactured? A similar reading can be applied to the software, and I think that is done more or less regularly when we talk about art.

The other side, the concrete one, is: what is it made of? Well, we open the black box and saying, “the computer is made of silver, copper, plastic,” right? And we begin to recognize this other dimension: that this object, in its concrete form, in order to operate or sustain these other practices or functions in its abstract form, goes through a process of profound detachment from the origins of the materials that compose it, to the point where those materials appear to become invisible.

NKA: True, even in art…

DR: Especially within conversations in the arts! There is a strong push toward immateriality, toward the intangible. No, that is precisely the trap, because at least today there is no interface that is not made up of an incredibly concrete set of materials. And if we stop recognizing those materials and set them aside, we run into a serious problem, not only epistemological or ontological, but a very real one: failing to see the consequences produced by the fabrication of these objects in territories such as Latin America. There is a very particular spark there that, to me, ends up igniting much of the artistic production that seeks technological disobedience, because it has to do with not generating a production that contradicts the discourse we want to articulate in the work. If your discourse has to do with decolonization, with making us aware of the environmental crisis, with the displacement of Indigenous communities, yet you are using these tools exactly as they were predesigned, then there is a profound gap in the discourse. It is not coherent with the tools we are putting into play.

I think many artists recognize this, which is why they move toward this other position of “I’m not going to buy it off the shelf, I’m going to make my own”; of taking “obsolete” technologies to provoke a different kind of response, such as “I’m going to resist the extractive and consumerist logic that innovation from Silicon Valley proposes,” or “I’m going to work with ‘less sophisticated’ technologies.” That is where, to me, a form of recognition takes place, one that only makes sense once you begin to unpack it, by acknowledging how these elements converse with one another. That is why I find it so interesting that Simondon was already saying this, even before we were talking about the chaos and crisis we are living through today. He was already proposing that it is not possible to understand the process of individuation of a technical object without recognizing these two parts. In that sense, we were already on a very productive path, even from a fully Western philosophy of technology.

Where did it stall? At what point did it become so complicated that it is impossible to say “this is what is happening”? I think that, from a Western perspective, there have been many attempts to reveal or provoke that conversation. Tactical Media is part of that, it comes close in some ways, but the reason I ultimately chose not to go down that path is that it is already too firmly shaped by a European logic.

It seemed very important to me to bring into the conversation, in this particular case, a reading that is much more sensitive to where these logics are situated and to how they converge from Latin America. In the end, I think Ernesto Oroza does this very well, because that is precisely the point: it is not the sophisticated idea of tactical media in the European sense of the term. Although one could perhaps say that practices of technological disobedience are, in fact, a category in themselves within tactical media. In my particular case, that is the reason why I do not want to turn toward that specific space [of tactical media], even though at first I did consider doing so.

NKA: Can you explain a little more about Tactical Media?

DR: Sure. “Tactical Media” is a way of naming artistic or creative practices that diverge from hegemonic forces, in this case, political and cultural ones. It is a proposal that emerged in the early 2000s from David García from Spain and Geert Lovink from the Netherlands, to name movements or forms of production characteristic of that first decade of the Internet, which sought to use it as a space not subject to censorship, horizontal in nature, and capable of producing a global village. They are not referring only to net.artbut they are very much fueled by what happens in the communities of net.art, which were already exercising a form of activism that, in those geographical contexts, had no real prior comparison, precisely because it was not subject to or limited by what the public sphere might otherwise be subject to or constrained by.

NKA: Public space that [ideally] is reflected in virtual media….

DR: It is something like a radical collectivity, pushing against hegemonic discourse and exceeding the institution. Of course, like public space on the internet, or the internet as public space, where placing a critique or a piece that in some way challenges the status quo, for example that of the museum institution or political campaigns, produces that radicality. The internet becomes the space that allows you to engage in activism, in this case hacktivism, through the use of those same technologies. Technologies as a liberatory object, so to speak.

David García and Geert Lovink have an email mailing list called The ABC’s of Tactical Media, which they circulated in the early 2000s among people in different places who identified that their practices resonated with the idea of tactical media. The idea of calling them “tactical media” rather than “strategic media” relates to De Certeau’s framework6, which proposes that the difference between the tactical and the strategic lies in the fact that the tactical is ephemeral. It is something that happens once, an opportunistic action in the positive sense. It involves being conscious of and sensitive to when and how to act at a specific moment. This stands in contrast to the notion of wanting to change the system from scratch or from within, which is another kind of divergent practice. Tactical media assume that an action may happen only once, but that, if it is precisely placed, that single moment can truly trigger a conversation, a shift, or a provocation. It is about being acutely aware of the political climate and acting from within it.

NKA: And there’s a bit of a risk that strategy [as opposed to tactics] becomes commodified and turns hegemonic, right?

DR: Exactly. Now, the big difference, of course, is that in Latin America this has always been a much less obvious conversation. The political climate of Latin America, its very political history, means that many of these proposals, even when framed as tactical gestures that appear and disappear and that can destabilize from within, operate under very different conditions. That is, the fantasy of freedom of expression, of non-oppression, the fantasy that if there are many of us, they cannot arrest us all. Well, we know that this does not work in the same way in Latin America. Here, they do pick us up and make us disappear. This is not Europe, it is not the United States, it is not Canada. We know that the conditions are considerably more complex from within.

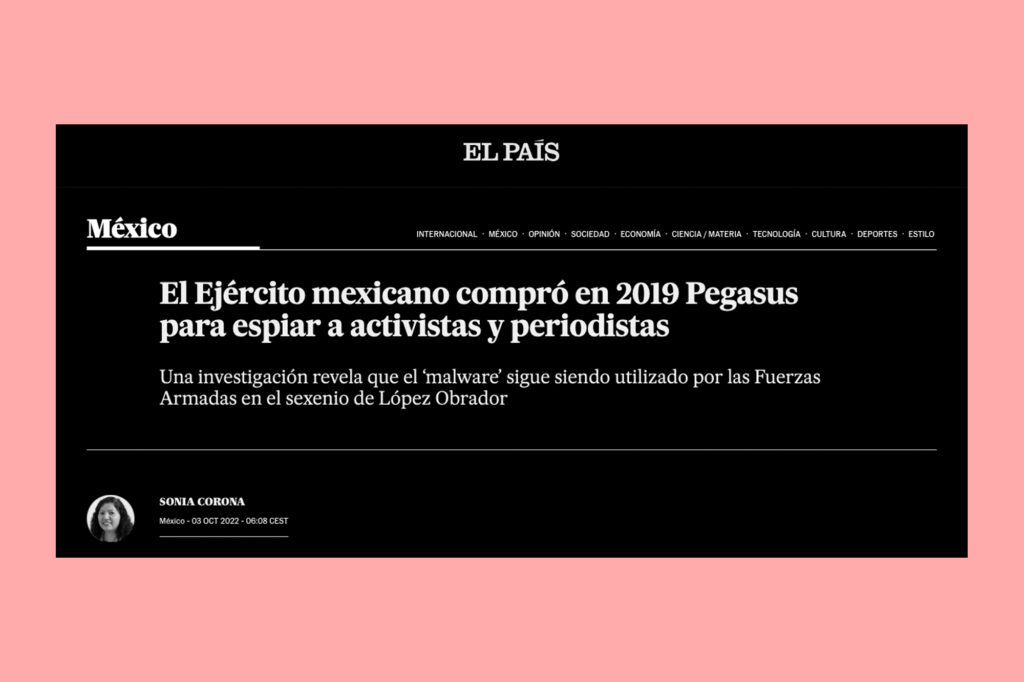

That is why the idea of tactical media does not seem particularly productive to me in this context. In my area of research, I am very aware that things in Mexico are not so simple. Mexico was the first country to acquire the Pegasus malware from the Israeli company NSO Group. The first buyer worldwide. The Mexican government! We are talking about a disparity that makes it impossible to discuss tactical media in the same way in Mexico as elsewhere. We are talking about one of the first cyberweapons [Pegasus] used against civilians, generating a network of surveillance that captures virtually all of your online activity.

In the second part of the interview, the conversation shifts toward ambiguity, piracy, and technological reappropriation as everyday practices in Latin America. From the Plaza de la Tecnología to xatarrera communities, Doreen Ríos reflects on other ways of making, sharing, and thinking about technology, questioning property, authorship, and hegemonic models of innovation.

[pronto]: Doreen Ríos (2/2): Ambigüedades, piratería y comunidades xatarreras—«Simbólicamente desmantelar los imperios monopólicos de la tecnología»

- Unpacking Mexican Media Art. Historical Materialism, Technical Objects, and Technological Disobedience is an essay that Doreen wrote as part of her doctoral studies. It is part of a writing process in which some ideas have, by now, evolved. You can download the PDF here. ↩︎

- This is a reference to DXARTS Qualifying Exam / Field One-History and Theory, a text that Nicolas wrote as part of his PhD qualifying exam, focusing on the historical and theoretical foundations underpinning the ideas behind Robotic Disobedience. Naturally, the ideas described in the text have evolved to the present day as well. You can download the PDF here. ↩︎

- It is about Technical Objects in Art. A Methodological Approach an essay Doreen wrote as part of her doctoral studies. As with Unpacking Mexican Media Art, this text is part of a research process in which ideas evolve. Regarding the definition of “technical object”, the author writes: “Technical objects, in the way that I am proposing we understand them, have the ability to transition from their initial purposes to a second life (Appadurai, 1986) through various means such as their reuse, reappropriation, and reinvention.” You can download the PDF here. ↩︎

- Some of the ideas related to “meta-tools,” as Doreen defines them, are found in Lev Manovich’s Software Takes Command (2013). ↩︎

- Roland Barthes formulates an “ontological desire” with respect to photography in Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography originally published in French in 1980. ↩︎

- Michel De Certeau formulates the distinction between “strategies” and “tactics” in The Practice of Everyday Life originally published in French in 1980. ↩︎

Responses