Leo Núñez: Discomfort, Footprints, Disobedience, and Complexity–«I believe all art should be more disobedient.»

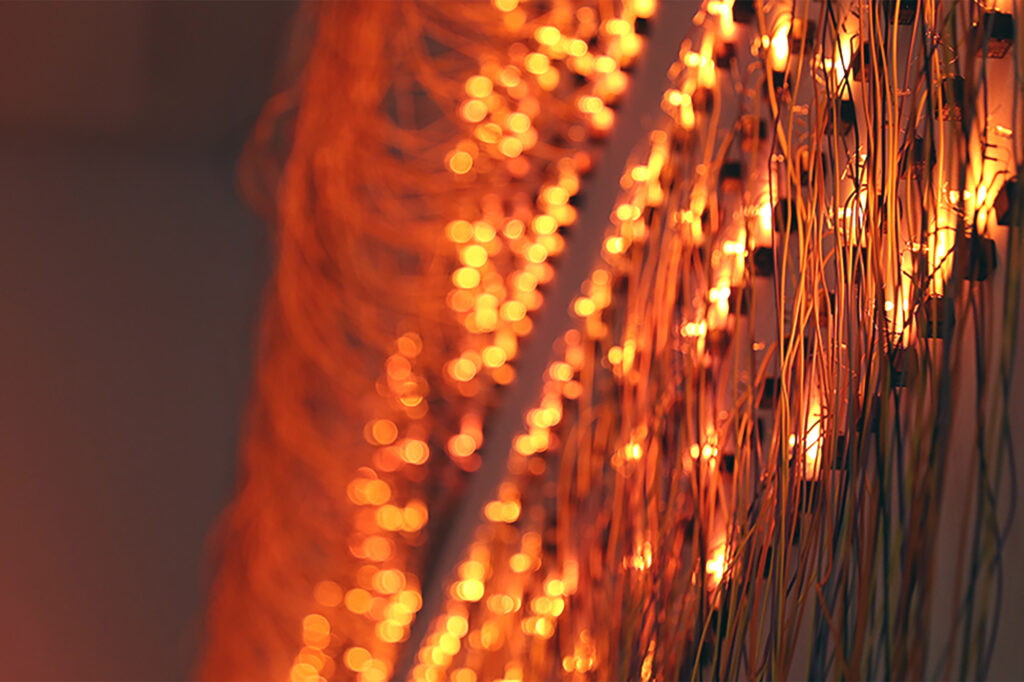

Cover Photo: Zoom on cables from Leo Nuñez’s “Lo recuerdo” (2016) installation. Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

In early April 2024, I took advantage of Leo Núñez‘s visit to Seattle to sit down for a conversation. The Argentine artist was at the McMahon Laboratory of DXARTS (University of Washington), collaborating with Juan Pampín on their work “Una y otra vez” (Time and Time Again).

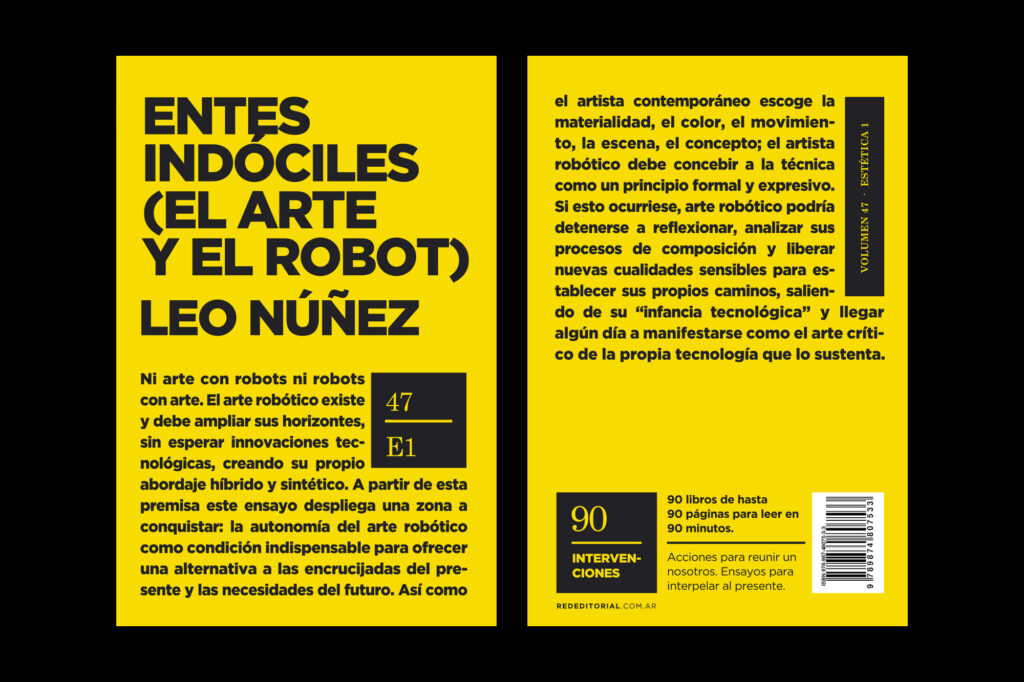

Leo, author of the book “Entes Indóciles” (Unruly Entities), has spent years working with robotics from a critical perspective that resonates deeply with Disobedient Robots. Before and after dealing with the stubborn, chaotic cables and mechanisms of their installation, we discussed how to think about robots beyond their functionality and how to think of technology from a Latin American perspective.

Nicolás Kisic Aguirre: Thank you so much, Leo, for making time for this conversation. I’ve been looking at some examples of your work—you have so much robotics-related work! My project is called Disobedient Robots/Desobediencia Robótica, and in a minute, I’d love to tell you a bit about what it’s about.

It’s about exploring, through art, a different way of relating to robots. Instead of thinking of the relationship as subject-object or seeing robots as tools—with this very Western, very “Global North” imperative that views robots as tools for production, consumption, surveillance, or war—it’s about trying to disobey that. Setting aside the robot’s functionality and thinking about how robots and humans can relate to each other differently.

Personally, it’s a kind of unlearning. It’s not that I’m saying, “Okay, from now on, my robots are like my children or my siblings…” It’s a process (of unlearning) that I feel could be greatly enriched by conversations like this one, especially because you’ve worked so much with robotics… and you’ve even written a book on the subject!

I wanted to start with Entes Indóciles, which is the title of your book and also the title of one of your works. It resonates with Desobediencia Robótica…

Leo Núñez: Yes, well, great. Entes Indóciles was a piece that came together in just one day in a small space, but the idea of the word stuck with me. Because an “ente” is an entity, you’re not quite sure what it is. It makes noise and doesn’t have a clear-cut definition, you know? When we say “robotics,” we already have a general idea of what we’re talking about, but…

…I do an exercise that I really enjoy with kids when I teach—I love doing this with them. I tell all the kids to close their eyes and imagine a robot. Quickly, the first robot that comes to mind. Done. Then I say, “Okay, raise your hand if you imagined a robot that doesn’t move.” No one. “Raise your hand if you imagined a robot without limbs.” No one. “Raise your hand if you imagined a paper robot.” No one. “Raise your hand if you imagined a robot that’s tired, greedy, or shy.” And no one raises their hand.

Then I say, “Alright, raise your hand if you imagined a metal robot.” And everyone raises their hand. “Raise your hand if you imagined a robot with a head…” and most of them raise their hands. With that simple game, you realize which way the imagination is shaped.

Afterward, I ask them, “Of those robots you imagined, who has ever seen or had a robot like that?” And no one can raise their hand because that imaginary is usually shaped by movies and television nowadays.

LN: I’d recommend you read Edgar Morin1, a philosopher and filmmaker who talks about collective imaginaries. With that little game, I establish that we all think about robotics in very similar ways and share the same collective imaginary. But I understand that art shouldn’t think about robotics in that style—it has to seek its own robotics. The moment has come—or rather, the moment arrived long ago—to consider what is at stake for art in robotics. Because, in the end, using certain forms of technology or certain technologies to do what the “Global North,” as you say, proposes is to endorse that vision. So when you talk about disobedient robotics, well, I believe all art should be more disobedient. More disobedient to all that… and that’s where we find ourselves in the junction, or the problem, or the paradox we have in the Global South of creating technology while criticizing the globalization of technology.

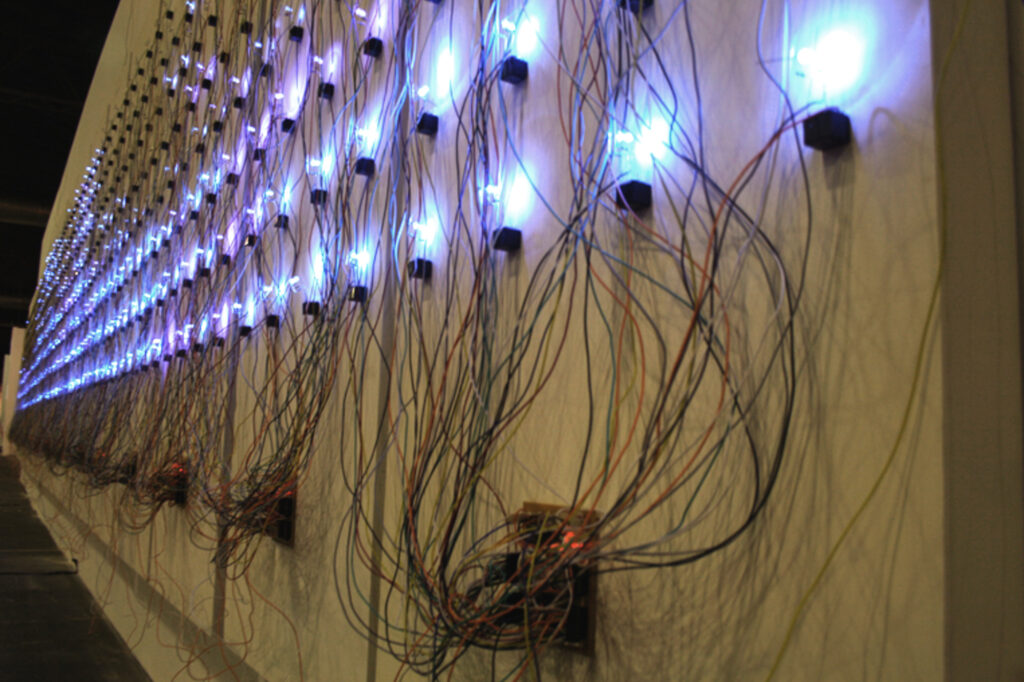

And, well, that’s what my work is about. Trying to be “disobedient” to that—to borrow your words—and seeking my own path. And sometimes my own path, my own way, isn’t comfortable for me. It really isn’t. I spend my time laying cables everywhere, and in many of my works, there’s this aesthetic of cable multiplicity and complexity… and honestly, I can’t stand cables anymore. I’m sick of untangling cables. It’s really uncomfortable for me to have to transport cables back and forth… In fact, sometimes I look at my pieces and I’m not even sure if I’m visually satisfied with how they look.

But it’s not about me. It’s about what I’m conveying with that multiplicity of cables, and I think that discomfort leaves traces in the work. It tells the story of a kind of technology more representative of my context—as opposed to a more black-boxed, hidden technology. There’s a term for that, though I can’t recall it right now. It has to do with coexisting with technology.

NKA: Like something pristine, perhaps?

LN: Yes, we use another word, but it’s along those lines. There’s a well-known Argentine philosopher who’s been gaining attention again recently, named Kusch2. At one point, he talks about airplanes. He describes how, when you board a plane, everything is done to make you forget that you’re inside an airplane. The little seat, they bring you a little snack, the tray table, someone walks by and serves you… and you lose the awareness that, in reality, you’re twenty thousand meters above the ground, at risk of everything falling apart, completely dependent on the technology working. So, there’s something about that constant concealment that doesn’t interest me—I’m interested in the opposite.

NKA: Maybe that’s what creates the discomfort you mentioned… could that discomfort be related to some kind of unlearning?

LN: Yes, it’s like erasing and starting over… when you make art. Because, once again, it’s about seeking technology’s own path within art. We can’t make art the same way the industry does. That’s why I’m unsettled when people talk about art and science.

It’s very difficult to talk about free art when there’s constant concern for scientific validation. That’s why I prefer to call it art with science. On one hand, as a play on words—thinking consciously3—but on the other, to say: I use science. It’s not that I need science to validate me. I’d rather take science as a tool and, by distancing myself from it, give myself the chance to question whether or not I even need that science. Because when you say art and science, it sounds like they’re walking hand-in-hand down the same path. It also gives science the chance to feel like an artist, you know? There’s this whole situation where new technologies always seem to compare or validate themselves through art. The first automatons that played the piano, played some instrument, or played chess—why did they play the piano? Why did an automaton write something back in the 1700s? It’s the same thing happening now with new technologies. They draw, they animate, they design things. As if, by placing themselves at the level of an artist, they’re validating themselves.

NKA: Proving they’re capable…

LN: Exactly. So, I don’t want to belong to that science. Because I have a lot to say about everything that overwhelms the land in the name of technological advancement. Since I have things to say, I can’t do art and science — at most, I can do art with science.

NKA: In a way, science is also a product of the “Global North,” isn’t it? And I’m not saying that’s negative or that it’s the enemy. But it comes with meanings and burdens that, if we take them for granted, we forget that there’s a lot to criticize there, right? In fact, I mean criticizing from lands that have been colonized. Ultimately, we live in places that have their own essence—Argentina, Peru, Latin America in general—but an essence that’s constantly struggling against what was imposed hundreds of years ago. I find it remarkable to propose that robotics can be a response. A response from the South to the North.

LN: Yes, it can be—like any other art form. It can be. The thing is, robotics is closely tied to technology. That’s why I say we should separate ourselves as soon as possible. When I see robotic art pieces that are just an industrial arm (NKA: Painting, right?) That does some little trick or its gimmick and shows nothing beyond that, they’re presenting me with a finished object and forgetting about the process that brought it there. About the object as a creator and what it represents. A robotic arm in the industry replacing workers and so on.

NKA: Right! And there’s already the dream—I don’t know if it’s everyone’s dream—but the dream or nightmare that robotics sometimes presents, whether through science fiction or even material reality, is the humanoid robot, isn’t it? The one that becomes indistinguishable from a human. Because it speaks perfectly. Today, we’re already seeing how they’re mastering language, and little by little, they’re starting to look more like us… I noticed that and thought, this anthropomorphization, in a way, strips away any possibility of having a different kind of relationship with robotics—of robotics having its own agency.

LN: Exactly. That’s why we need to be more disobedient. More disobedient against all of that. Look at what’s happening, for example. If you watch videos in the style of Boston Dynamics… Fifteen years ago, those videos showed robots in parking lots, demonstrating that they could run, or in jungles… clearly designed with military applications in mind. If you observe the progression, these robots are increasingly being presented in more familiar environments. It’s as if, little by little, we’re being eased into the idea of coexisting with them.

There’s a philosopher who says we’re already in the age of robotics at the level of familiarization. The only thing missing is the robots themselves because, theoretically, we’re already prepared for each of us to have a little robot at home and say, “Bring me this,” “Fetch me that,” you know? And it’s always framed with the idea that they have to be useful, that they’re there to serve some productive purpose. But sometimes productivity isn’t about objects; it can be cultural. Symbolic. Conceptual.

NKA: Right, and does your work aim to explore that idea?

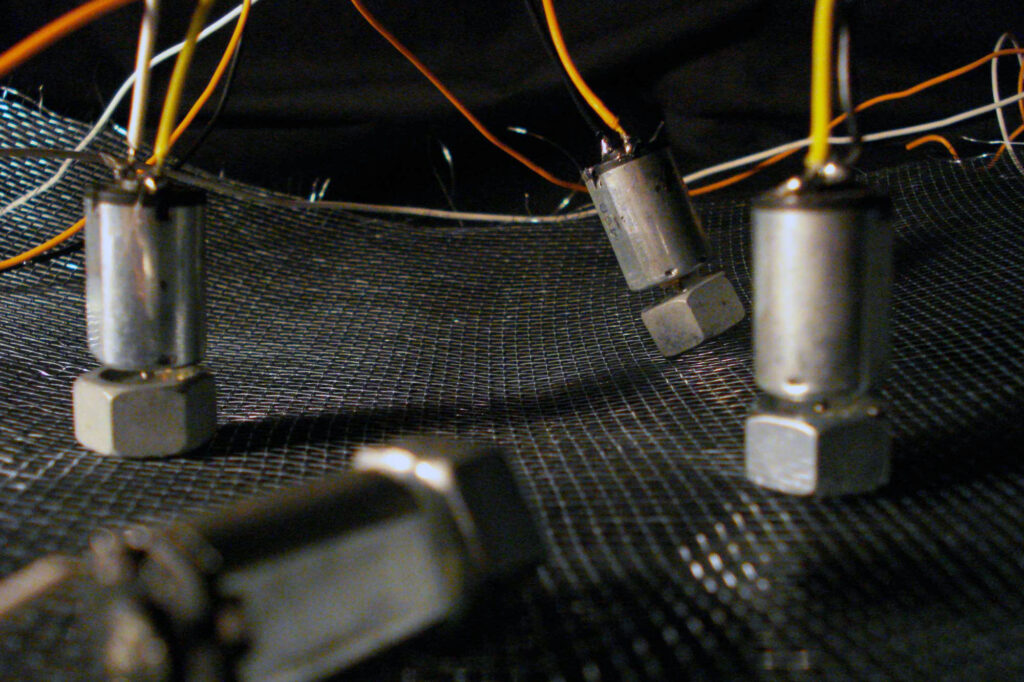

LN: That’s the direction I’m trying to go in. For example, with Entes Indóciles, my goal was to create the smallest robot I could. But not smallest in terms of size—rather, I was searching for that threshold where you look at an object and say, “Ah, that’s a robot,” versus when you look at something and just see a thing that moves, nothing more.

NKA: Ah, I see—like identifying the single additional gesture that would turn something into a robot.

LN: Exactly. That’s what I was searching for.

NKA: And what was that gesture?

LN: The robot ended up being just a motor with a nut attached to it. That was the object, nothing more. It changed when I added a sensor that pointed at my body and, depending on whether I approached or not, the object moved, jumped… I had programmed a small response. So, there was this idea of communication between my body and that other body. And with just that single change, a nut with a motor became a robot.

NKA: Right! And was it just one nut with a motor, or were there many of them?

LN: No, at first, it was just one. But later, there were many.

NKA: I find it interesting that in your work—I don’t know if it’s always the case, but often—after searching for the individual entity, there’s a multiplication. What do you discover in that process?

LN: Well, I guess I feel more comfortable in complexity. I feel weaker in singularity. I like things when they’re complex and situations emerge from that complexity. I enjoy that. I also like it when my work shows traces of labor—the artist’s hand behind the creation. In the piece we have here4, with the bicycle wheels, the first thing you notice is that someone worked hard on it. There are so many parts, and there’s a kind of imprint there—something latent, present—that’s very different from the impression you get when you walk into a store to buy a phone, where all the devices are lined up, and you never get a sense of how they were made or who made them. So, there’s a pursuit not only of craftsmanship but also of revealing that someone put in the work. The artist’s imprint, even in technology.

NKA: Something that feels very Latin American, I think, right?

LN: I don’t know. When I started many years ago, we didn’t have many references. I don’t want to take credit for it, but it’s a line of work I’ve been pursuing for a long time. I’m not sure—there weren’t really any references when we started.

NKA: Right. What I mean by Latin American is that we’ve been through several crises. (For example,) Argentina is currently in a brutal crisis, and Peru goes in and out—we’re always in crisis. Sometimes, the crisis forces us not to grab the electronic device, the gadget that already comes in its perfect little box, but instead to make it ourselves. And in that making, often out of sheer necessity, the maker’s hand is reflected, right? And often, with parts that have nothing to do with each other—Frankensteins…

LN: Yes. I recommend you read an old text by Rodrigo Alonso, an Argentine curator, called Elogio de la low-tech5. What he says is that using technology isn’t about resignation. It’s about valuing other things.

Likewise, when we planned to make the works here6, we initially planned to buy a bunch of ready-made things. Over time, we realized that the work became more expressive and aligned more closely with what we wanted by making each part ourselves.

So, what am I getting at with this? When you buy something, not only are you endorsing that industry of production, of black boxes and all that. You’ll also find that many people have done the same. Because it’s a product designed to be used in a certain way. When you start producing your own things—and not because you say, well, I’ll just slap this on here (as decoration, superficially)—no. Quite the opposite. You do it because the work needs you to produce certain things for it to become more expressive, more conceptual, or more symbolic in each of its parts… and then you start acquiring certain skills.

Another thing is that a piece… there are two or three things. Sometimes, you don’t have those skills, and maybe there are times when you don’t have the resources to buy whatever it is you need. But if a piece can survive your lack of skill to make something, and you think, Oh no, I can’t do it, well, you start breaking it down and focusing only on the essential part, getting to the core of the matter. (You think,) I want to buy six projectors, and maybe you do have the money. But as you go along, you realize you can solve it with just one TV. That is, you start refining the entire piece. And if the piece survives all that, you’ll have a much stronger work than one based primarily on what you can afford or allow yourself build.

NKA: In other words, if there’s no challenge, or if everything is too easy, maybe the expression gets diluted.

LN: Exactly. You end up sticking to your first… it’s like reaching the end of the piece without ever really traveling the path. When you just say, “Okay, I’m going to make this thing,” and suddenly, that’s it… It’s kind of like what happens when you work with other people on a project—like hiring engineers, for example. You hire two engineers to help you build a device, and the guy asks you, “What do you want?” (And you reply), “Well, I want it to have six wheels, move like this, and do that.” Okay, the guy makes exactly that, but what happens is you’re already telling him the final result before you’ve even started the journey.

Because during the production process, you discover so many things that sometimes make the piece end up being nothing like what you first imagined. But in the end, you get a much more refined work, both technically and conceptually, because you’re working through everything as part of that process.

So, when you buy something that’s already finished, something similar happens. I mean, you get to the end before you’ve even started, and you miss out on that whole process. And often, that process is richer than the original idea.

NKA: (That’s super insightful because, in a way,) I was thinking about how, in reality, refusing to go straight for the black box and instead making things yourself is a form of technological disobedience. It ultimately changes the way we relate to our objects. But what’s beautiful is that you’re describing how, for you, that different kind of relationship gets broken down, and its essence lies—at least in part—in the process.

When you buy something that’s already finished, […] you get to the end before you’ve even started, and you miss out on that whole process.

LN: I go back to this author I mentioned, Rodolfo Kusch. He has a whole way of thinking, and it has a lot to do with the verb “to be”—ser or estar in Spanish. He talks about the Latin American concept of “estar siendo”—“being in the process of becoming.” One kind of being has to do with a finished object, a completed piece, a work that gets hung in a museum and just is there. Kusch says that Latin Americans, because everything is handed to us or comes from elsewhere, can never fully reach that state. So, we can never just be. What we’re always doing is “estar siendo.” We’re constantly in that state of becoming. I’m simplifying it a lot, but that’s what he means by “estar siendo.”

NKA: That’s such a beautiful idea! You mentioned earlier the importance of process. I think sometimes we say the process is over, but really, a process never ends. When you say it’s done, it’s because it already “was“. It’s no longer “becoming.” I feel the same way about my work—I always say that none of it is ever really finished.

(In Latin America) What we’re always doing is “estar siendo.” We’re constantly in that state of becoming.

LN: That’s why it’s not just about a single piece. When you start out, you think the work you’re creating is the piece—like, “I have to put everything into this because this is me.” But over time, you realize it’s not just one piece. It’s many works. If you look at my first piece and my latest, there’s a change. Even in me, there’s a change. I’ve grown older, I think differently, I care about different things, my training is different, my tools are different. It’s all one long journey. That’s why it’s important to think of yourself as an artist, right? To ask yourself, “What kind of body of work do I want to create? What kind of artist do I want to be?”

NKA: Without giving in to the temptations… I mean, there’s the art market, the festivals, the events, right? They create expectations. Sometimes you just want to be in the festival. You want to be in that gallery, in that space. And that can end up shaping an artist into something far from what they might have chosen for themselves in their own process.

LN: Exactly, so the important thing is that, right? What kind of artist do you want to be? And what’s interesting, what’s important for me at this stage, awards or no awards, shows or no shows, it doesn’t really matter… (In the case of galleries), well, if someone picks you up and you’re doing what you think is right, that’s fine. But the most important thing is to be honest with yourself. That’s the most important thing. For me, perhaps, the most difficult part. What I do in art is very personal, and I don’t depend on it to make a living. So when I create, I create out of desire. For pleasure. For example, working with Juan (Pampín). I really wanted to work with Juan for years, it happened, we started a year ago, and here we are.

NKA: Juan, in a way, introduces sound into your work (in the collaboration). You’re not a sound artist; you don’t define yourself as such. This makes me think of something a bit tangential, but it’s interesting. Returning to robotics, (I start thinking) about the robot’s voice. Again, we have the collective imagination, as you mentioned at the beginning, the idea that the robot speaks. And if it speaks, maybe it’s already a robot. According to the collective imaginary, (the robot) answers you, right?

But in your work—and perhaps it’s better that you’re not a sound artist—you develop a robotic voice, but one that probably expresses itself in (another kind of) way. The other day we were talking, I remember you also mentioned cybernetics. The communication system between multiplied entities, do you think this develops a robotic voice?

LN: The idea of voice has to do with the idea of command. The word robot, which comes from this… I don’t know if you know where it comes from…

NKA: Yes, from the Czech play7…

LN: Yes, they were workers, but they weren’t made of metal, they were made of flesh, of bone, of skin… but the voice of command was easy. So, the idea that the person listens to you and responds has to do with making life easier for us, right? In reality, it speaks of our precariousness…

NKA: Right, our lack of willingness to relate…

LN: It’s about comfort. It’s all to make us more comfortable and empathize more quickly. I mean, it’s related to that. In my works, I have a lot of sound, but these sounds are mostly produced by machinery… by the motor and so on… and it has its expressiveness. In some works, I intentionally drag things across the floor and file the edges to make more noise, you know? That’s intentional. In fact, the first works I did with relays8 were purely sonic, with no image, nothing, no light, just sound in a space. I don’t know why, but the work led me to that. Even though I’m not a sound artist, the first thing I did was sound works.

And about the communication between objects (cybernetics). It’s mostly about generating complexity and communication among them. That’s where I find a space, I’m not sure if it’s comfortable, but it’s a space that interests me. This idea of working in complexities. What I mean is, when objects start to relate to each other, dialogues begin to emerge. They can be created by light, others by sound, data, interactivity with the body of the spectators, I mean, by chance. Dynamics of the work start to emerge. Sometimes I produce the possibility of disturbing those dynamics with interactivity, but I’m interested in that. Unexpected situations happen, not expected by the spectator or by me, but they happen. And there’s something that I think is rich, it enriches me, it even entertains me.

When objects start to relate to each other, dialogues begin to emerge. They can be created by light, others by sound, data, interactivity with the body of the spectators, I mean, by chance. Dynamics of the work start to emerge.

NKA: Yes, I think the unexpected also expresses a certain agency, I don’t know if it’s of the system, or the ecosystem, or the “mechasystem.” And also, going back to what we were talking about, how today we see that language, especially English, is—what I would call—“imposed” on robotics, on algorithms… especially with the recent advancements in artificial intelligence9. This brings us back to relating to the robot, just as Karel Čapek initially defined it, as forced labor, through “command,” as you said. It “blinds” us from the possibility of listening to robotics (robots) through their own communication systems and their own expressions. In one case, there’s a hierarchy, and in the other, perhaps not. We don’t have to literally understand what happens with that system, but we should be surprised, explore, and discover…

LN: Yes. That’s why I go back to the beginning… the Entes Indóciles (unruly entities). Indocilidad (unruliness) escapes the subject’s control. So, the Ente Indócil is that which I don’t quite understand, but I know it’s escaping my control. That’s why they’re called Entes Indóciles. Because those two things are put into check. “Ente,” (entity) the material idea of that object, robotic, mechanical, mechatronic. And “indocilidad” (unruliness) the idea of communication. That’s why cybernetics comes into play, which is basically that. The study of behavior in animals and objects… So, that’s why this two-word concept, which encompasses all kinds of noise, both material and communicational.

NKA: These words of yours… I think they’re an excellent way to conclude our conversation. I think we could keep talking for hours, but (time and space limit us)… Thank you so much, Leo!

- Edgar Morin addresses the concept of collective imaginaries in several of his books, but one of the most relevant is The Method, Volume 5: Humanity of Humanity. In this book, Morin explores how collective imaginaries influence culture, identity, and the construction of social thought. He also touches on this topic in Introduction to Complex Thinking, where he develops the idea of how imaginaries shape our perception of the world and our way of knowing. ↩︎

- Rodolfo Kusch’s reflections on alienation and the distortion of the perception of reality in the context of modernity and technology can be found in works such as Geocultura del hombre americano and, specifically, in La negación en el pensamiento popular (Chapter 8: La fórmula del estar-siendo, p. 649). ↩︎

- In Spanish, Leo proposes “arte con ciencia” instead of “arte y ciencia.” The connection between arte-con-ciencia creates a play on words that could translate to “conscience and art.” ↩︎

- Leo refers to “Una y otra vez,” developed in collaboration with Juan Pampín and first exhibited in April 2024 at the DXARTS department gallery at the University of Washington, Seattle. ↩︎

- “Elogio de la low-tech. Historia y estética de las artes electrónicas en América Latina,” by Rodrigo Alonso (2015). In English: In Praise of Low-Tech: History and Aesthetics of Electronic Arts in Latin America. ↩︎

- In the context of the Time and Time Again exhibit at the DXARTS gallery. ↩︎

- Rossum’s Universal Robots (R.U.R.) by Karel Čapek (1920). Čapek is credited with introducing the term ‘robot’ into the world’s vocabulary. Derived from the Czech words ‘robota’, and ‘robotnik’ (which relate to forced labor or servitude), this word first appeared in his play in 1920. ↩︎

- A relay is an electronic device that works as a switch activated by an electrical signal. ↩︎

- I refer to the advances in natural language processing (NLP), which allow ChatGPT and many other Large Language Models (LLMs) to function so naturally. ↩︎

Responses